Lincoln Park Zoo scientists labor year-round on research projects designed to help humans learn more about animals in many different contexts. This type of work allows the zoo to better care for the individuals that reside here. Visitors don’t necessarily see all the effort that staff put into projects like these—but can often see the results. For the animals in our care, this translates into more dynamic living spaces, improved enrichment, and actions that make life better, safer, and more natural. For animals in the wild, this leads to improved understanding and better conservation strategies and outcomes.

Dig Pits, Deconstructed

The naked mole rat habitat at Regenstein Small MammalReptile House is a fascinating place, although you may not realize it at first glance. Most visitors take a peek at these animals huddling in their burrow and then move on without realizing how unusual and interesting these small, hairless rodents really are—and they may not realize all the surprising science going on in the habitat they’re viewing.

About Naked Mole Rats

Naked mole rats live underground in the eastern part of Africa, and are incredible because they can go without oxygen for 18 minutes, have an extremely high pain tolerance, and live up to 40 years. They are resistant to cell mutation, meaning that they have a natural immunity to conditions like cancer. Naked mole rats are the only mammal that is eusocial; their society resembles that of certain insects who all work together for the good of the colony (think ants and bees). The workers are controlled by the queen not by pheromones, as happens with insects, but through behavior. These naked mole rats live exclusively in complex burrows that they dig together to expand.

Designing a Dig

Digging, for naked mole rats, is a social activity done in an assembly-line formation. One digs, several more sweep the dirt away, and one “volcanoes” the dirt out of a hole in the ground. However, in zoos, these animals traditionally live in various chambers connected by tubes; the habitats do resemble a naked mole rat burrow—but their fixed design has limitations when it comes to new space formation through digging. Naked mole rat burrows are constantly changing and can go off in many directions.

“Naked mole rats’ sight isn’t very good, but they have a really good sense of smell and they can sense vibrations through their whiskers and toes, allowing them to communicate through touch and map their spaces,” ZooMonitor Research Assistant Natasha Wierzal of the Animal Welfare Science Program notes. “It can be very hard for us to imagine what their world is like— we’re missing so much input that they use on a daily basis.”

So, Lincoln Park Zoo scientists and animal care staff began to ask what would happen if naked mole rats got more expansive opportunities to dig. And this required some ingenuity to create.

Lou Keeley, zoological manager, put together a prototype; he then tweaked it and worked with the facilities team here to build the current version. Animal caretakers connected the resulting dig box to the colony’s main habitat by a long tunnel that prevents dirt from being transferred back, ultimately designing and improving three models of dig pit boxes based on safety and behavioral data collected with the animal observation app ZooMonitor.

The researchers considered how the naked mole rat behavior changed from their original habitat design to each of the different types of digging opportunities the naked mole rats were offered as the design evolved.

Promising Results

First up—they dug! Naked mole rats at Lincoln Park Zoo had never dug through substrate and yet they jumped into action immediately.

As it turns out, naked mole rats exhibited more social behavior after being exposed to the dig pits. The animals also explored more, possibly because of the exciting new smelling and touching opportunities. Researchers also found that aggression in the colony decreased, while affiliative behaviors (which enhance unity) increased. The rodents also tried to dig at areas of their habitat that weren’t movable less often with the true digging option available.

Ultimately, researchers found that providing the naked mole rats with firmly packed clay allows them to perform their assembly-line method, which helps to reinforce social structures within the group, enhanced their wellbeing the most. This makes sense given that they evolved in areas of hard, sun-baked clay.

The results of the project were shared at August’s Association of Zoos and Aquariums national conference, hopefully inspiring other institutions to learn from our research and try this at their own zoos. “Showing that naked mole rats want to dig isn’t groundbreaking research,” Wierzal says, “But it’s good to have data that shows that you can do a simple thing that makes a significant impact for the better of both individual and colony welfare.”

Care and Welfare

Today, the naked mole rats have constant access to the dig pit. It’s refilled with soil every other week. “Animal care staff have made it part of their routine care,” Wierzal says. “Every time it’s refilled, the naked mole rats get a burst of excitement. They dive in again, map out more areas, and dig new patterns. We’re able to add new enrichment and obstacles for them, too. And now this project has turned into a million other questions we’re eager to answer with additional research.”

So, the next step is naturally to keep analyzing data, and to learn more about the naked mole rats through the opportunities that have arisen from the inclusion of the dig pit. For example, staff can look more closely at how tunnel excavation opportunities versus simple digging affects their welfare and social structures. They can add items like rocks to see how the naked mole rats react. “The care team is excited to build upon this and see what else we can do,” Wierzal says.

Primate Perceptions

Recently, Lincoln Park Zoo researchers studied the color preferences of primates, in a way that can help inform future cognitive work done with three different species.

On Colors

Colors influence people’s emotions in many ways—we find some calming and consider others to be warnings, and we feel certain ways about different hues based on social, cultural, and personal preferences. Nonhuman primates, who share a common ancestry with us, are no different.

In fact, color plays an important role in primate social development. Different colors convey different types of information to animals. For example, primates have evolved to detect certain colors associated with the foods they eat, like fruits and flowers; they may also use color to recognize and attract members of their own species. However, individuals also seem to prefer certain colors. Resident silverback western lowland gorilla Kwan, for example, clearly favors blue.

The Experiments

Recently, scientists at Lincoln Park Zoo wanted to explicitly investigate the preferences for distinct colors exhibited by certain primates. “The preferences and biases of primates have important welfare implications. Learning more about what attracts their attention and what they prefer, even with basic stimuli such as colors, allows us to enhance the care we provide. At both the species and individual level, we could design enrichment items, positive reinforcement training sessions, and even future exhibits with their preferences in mind,” Jesse Leinwand, a researcher with the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, says.

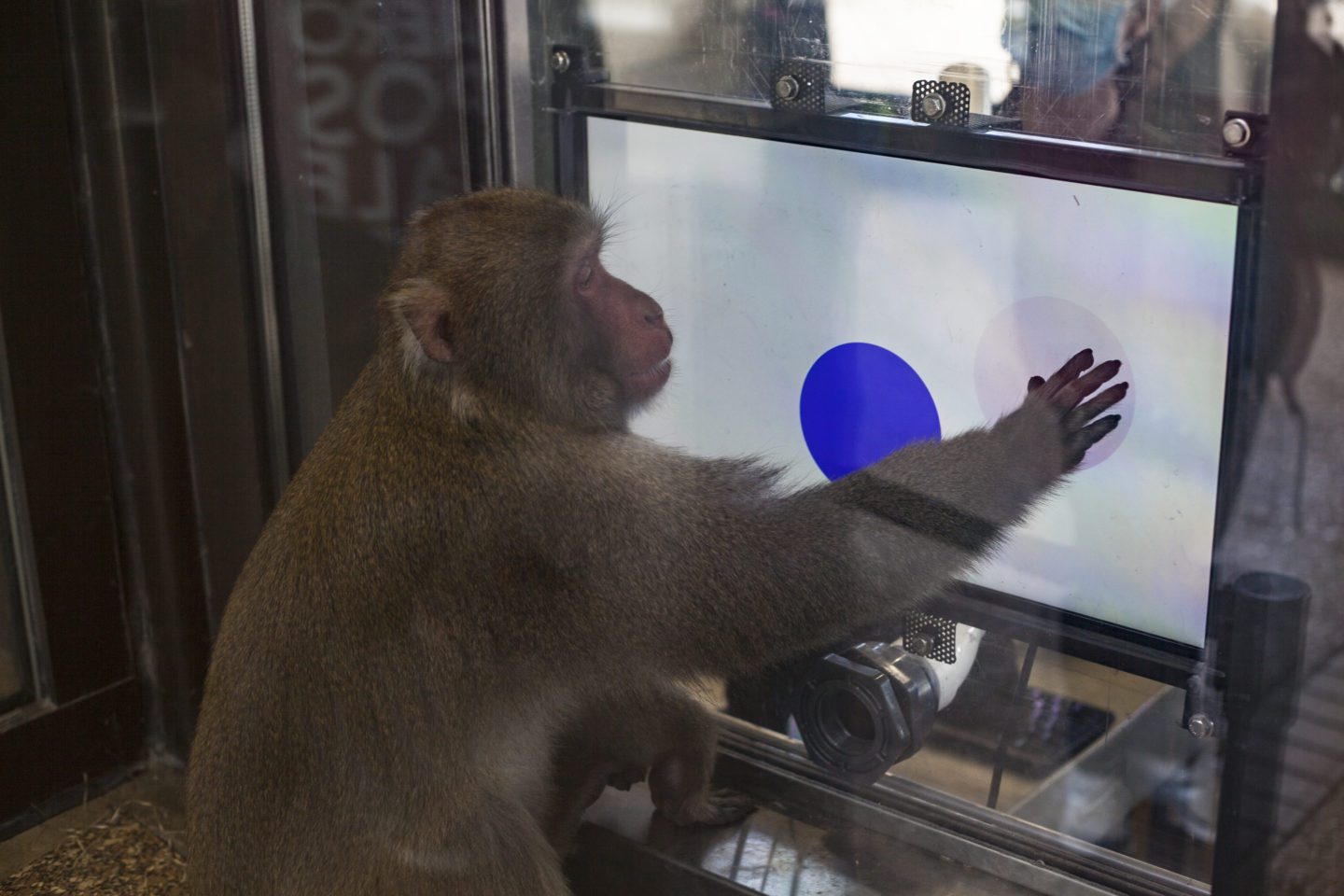

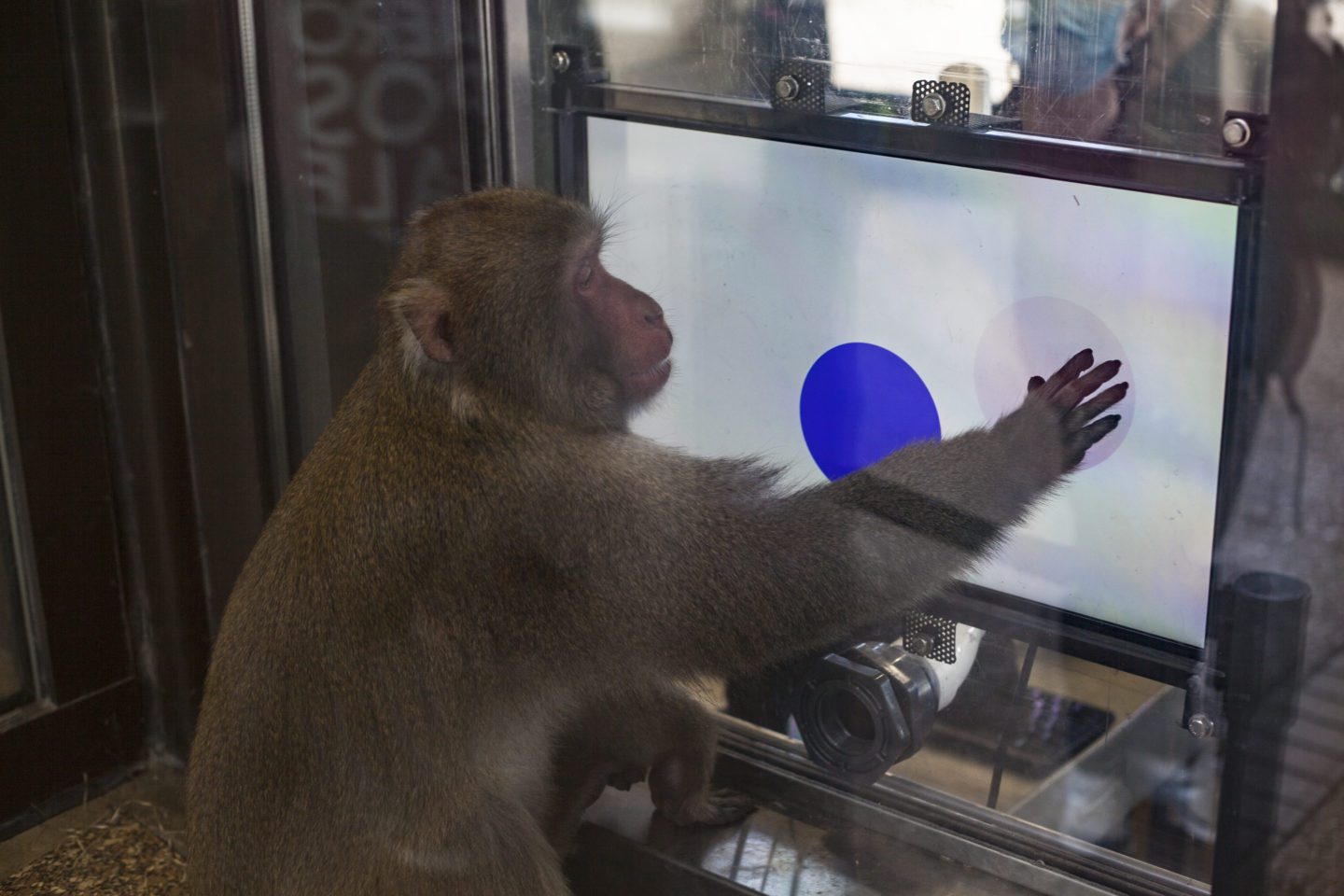

So, they did two separate experiments, presenting seven chimpanzees, 11 western lowland gorillas, and 10 Japanese macaques with pairs of colors on a touch-screen display. The two experiments helped scientists determine whether the colors that captured the primates’ attention fastest were also their preferred colors, and how these preferences varied between the three species and 28 individual primates.

Primates could choose whether or not to participate, so any animals that preferred not to do the tasks did not have to. They receive rewards for their participation and touch-screen tasks are often changing, so the studies can be fun and enriching for them.

“One really exciting component of this study was that it was the first study that one of the three-year-old gorillas, Mondika, participated in,” Leinwand says. “Since then, we’ve also been able to include his half-brother, Djeke, in touch-screen tasks, with all nine gorillas in Kwan’s group now taking turns working on the touch-screen Monday through Friday.”

In the first experiment, the scientists conducted a test using what’s called a dot probe attentional bias paradigm. Basically, the primates looked at two squares of color for 300 milliseconds before they disappeared. Then, a dot replaced one of the colored squares, and the primates touched the dot to receive a reward. Participants will touch a dot faster when it replaces a stimulus they are already looking at, so researchers can gauge where the primate’s attention was located at the time when the squares were replaced by the dot.

The Results

What did zoo researchers discover? Well, it turns out Japanese macaques showed biases toward red and to a lesser extent, magenta, which makes sense since they have red parts on their bodies that offer social cues and sexual signals to other macaques. Gorillas and chimpanzees gave their attention to navy and black most frequently, and of course, these colors align with their own physical appearances.

In the second experiment, zoo staff used a forced choice paradigm. In this type of test, the primates looked at a pair of colors until they selected one. Following this, researchers discovered that all three species picked red more often than other colors. However, chimpanzees on an individual level didn’t pick red significantly more often than their second-most chosen color, and gorillas also chose black and navy. The bachelor gorilla group showed a bias toward black, although a few did not seem to care.

In general, in the second experiment, none of the species seemed to choose the colors plum and cyan. Most macaques showed a clear preference for red—except one. Unsurprisingly, gorilla Kwan picked navy blue most often, a persistent preference researchers had seen before that led him to repeatedly incorrectly select blue before red in a sequencing task.

Scientists did learn a few important things from this research: first, for the many other researchers around the world working on cognitive projects involving nonhuman primates, we can advise that they be wary of the color red and how it might skew results. Colors might influence these species in ways that could bias the results of studies that aren’t looking specifically at color preference. So, using grayscale images might be a better option in some cases.

Next, Fisher Center researchers plan to explore the idea of social attention, investigating whether the primates can recognize their neighbors in Regenstein Center for African Apes, and if they show more attention to familiar or unfamiliar members of their own species. All of this work helps us better understand the minds of primates and make informed decisions about how to improve their care.

Misunderstood, Marvelous Bats

Most people either love or hate bats, but these animals— sometimes called “rats with wings”—get a bad rap in media and pop culture. They may seem scary, but they’re valuable members of their ecosystems. Lincoln Park Zoo’s Urban Wildlife Institute has been researching them for years in hopes of learning more about bats and about how to make sure these beneficial species are thriving in Illinois.

Not So Spooky

When you think of bats, you may picture small, dark, mysterious creatures of the night swooping down on leathery wings to capture wriggling prey with sharp teeth, using extra senses humans don’t possess. They’re fond of shadowy places, they’re often evoked in horror films, and they’re associated with vampires, which makes them popular icons around Halloween, the spookiest season of the year. There’s even a name for the fear of bats: chiroptophobia.

These fascinating little animals have long been misunderstood by humans, although in recent years scientists have been spreading the word about how beneficial bats can be as pollinators and insect-control specialists (each one can eat thousands of insects per night!). Hoping to improve their status and dispel some of the myths around bats, researchers at Lincoln Park Zoo’s Urban Wildlife Institute (UWI) started a research project to learn more about bats in Illinois starting around 2013. You see, back in 2010, UWI launched a biodiversity monitoring project in the Chicago area to understand urban wildlife. They use cameras at more than 100 locations to target terrestrial mammals, to understand the long-term changes urban wildlife populations are going through, and to learn more about animal habitats in a way that informs urban planning. However, if you know anything about bats, you understand that that this kind of setup may not be the best way to go about getting information on them. They’re too fast, they’re too small, and they fly.

Gathering Intelligence Through Innovation

But zoo scientists also knew it was vital to get basic information about bats in Illinois, including which species were living here, especially as white-nose syndrome became more and more of a threat. This fungal disease, believed to have entered the U.S. through Europe around 2006, has been catastrophic for North American bat populations. A 2021 study in the journal Conservation Biology estimates that the disease killed 90 percent of three North American bat species (northern longeared, little brown, and tri-colored) over a two-decade period.

So, researchers here at Lincoln Park Zoo, in conjunction with partners like Chicago Wilderness and the regional Bat Working Group, added an extra layer of observation to see if they could figure out how local bats were responding to the threat.

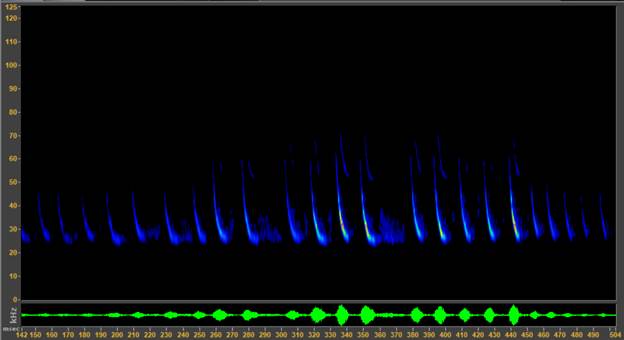

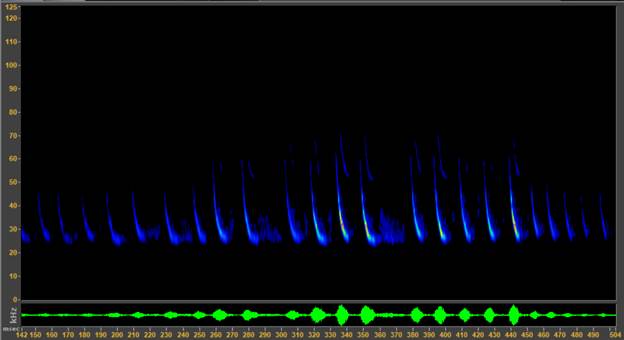

“We can’t take pictures of bats, but we can record their echolocation calls as they fly around,” Urban Wildlife Institute Assistant Director Liza Lehrer explains about the process they now use. “These calls are ultrasonic, so they’re above human hearing levels, and we have to use special microphones to capture their sounds. What’s really neat is that, although they’re hard to observe naturally, when we record their sounds we can visualize the recordings with a spectrogram to see characteristics unique to each bat species.”

In this way, they have been able to detect which species are located in different areas, and this has provided a wealth of knowledge regarding the numbers, habits, and populations of the eight bat species that call the Chicago area home. But that isn’t the only method UWI scientists are using to understand the trends that affect local bats. They’re also getting help from community scientists. They’ve been working with local natural area stewards from organizations like the Chicago Park District, whose volunteers have been trained to monitor and record bat activity in their own territories.

The Work Continues

Not only does this work assist the scientists at UWI, it also provides an opportunity for those volunteers to spread the word about the good that bats do. For example, stewards at West Ridge Nature Area often hold community events like “bat walks,” inviting local residents to come along, enjoy some nature, and learn about the essential role bats play in thriving ecosystems, from pollinating crops to providing guano for gardens.

UWI is finishing its 10th sampling season for bats, and the monitoring work continues. In the meantime, efforts like the above to upgrade the status of bats in the public eye appear to be working—at least on an anecdotal level. “Bats are the species that I’ve worked with over the years that people have been most excited about,” Lehrer says. “They’re polarizing, but many people are fascinated by them. They’re benefiting from this project because people are realizing the conservation importance, along with all the benefits they can provide. A lot of folks’ attitudes have changed.”