Those of us who live in cities like Chicago don’t necessarily think of conservation happening here. Conservation is reserved for exciting, far away, charismatic animals like the ones you see at designed habitats inside Lincoln Park Zoo—rhinos, lions, giraffes, gorillas, chimpanzees. Why bother about the squirrels, rats, and pigeons that call urban environments home? We see them every day, and they can be nuisances. They may even seem dangerous, under certain circumstances.

Even within conservation circles, there’s a hierarchy. Studying rats in alleys isn’t always seen as being as important as studying elephants in the savanna. Catching a view of a white-tailed deer sprinting across a street doesn’t have nearly the same scientific cachet or emotional impact as glimpsing mountain gorillas in remote African forests to some.

Yet one might argue that the animals commonly found in cities have more to teach us, and they can be as fascinating as any animal in the wild. “They’ve found their way here, they’ve set up their homes here, and they figured out how to live around humans really successfully,” Urban Wildlife Institute Assistant Director Liza Lehrer notes, pointing out that it’s a misconception that animals don’t belong in cities.

This image of a raccoon standing on its hind legs was taken by UWi’s motion-triggered cameras.

After all, there’s no denying that the most successful animals in the history of the planet—the ones who have done more to shape the planet to its liking than any other species—are human. Wildlife that has adapted to live and even thrive in that changed world deserve our respect. They have become an important part of our communities, for better or for worse, and we need to learn how to live with them.

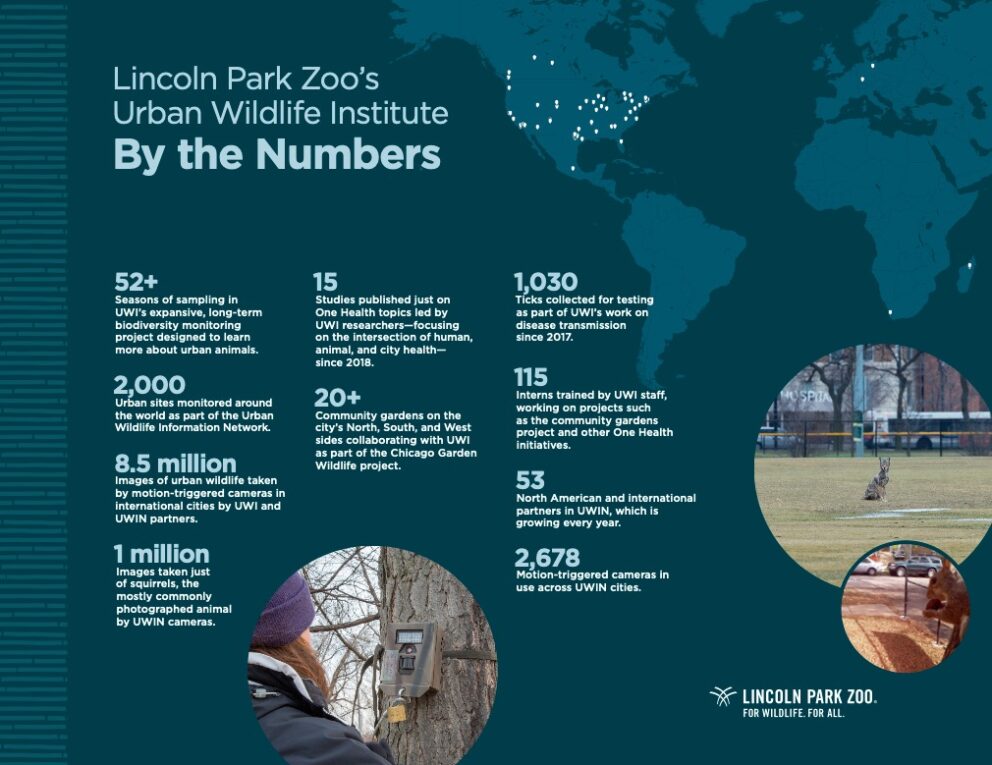

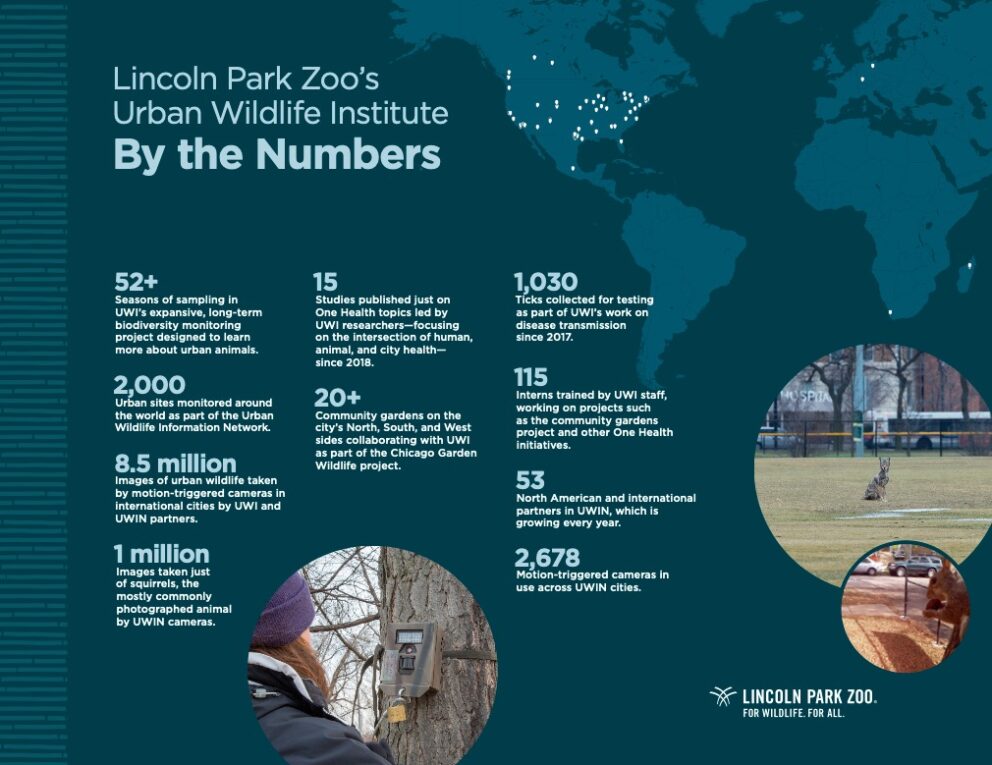

That’s why the Urban Wildlife Institute exists, and why it has been studying animals across North America since 2009 and on other continents through the Urban Wildlife Information Network since 2017.

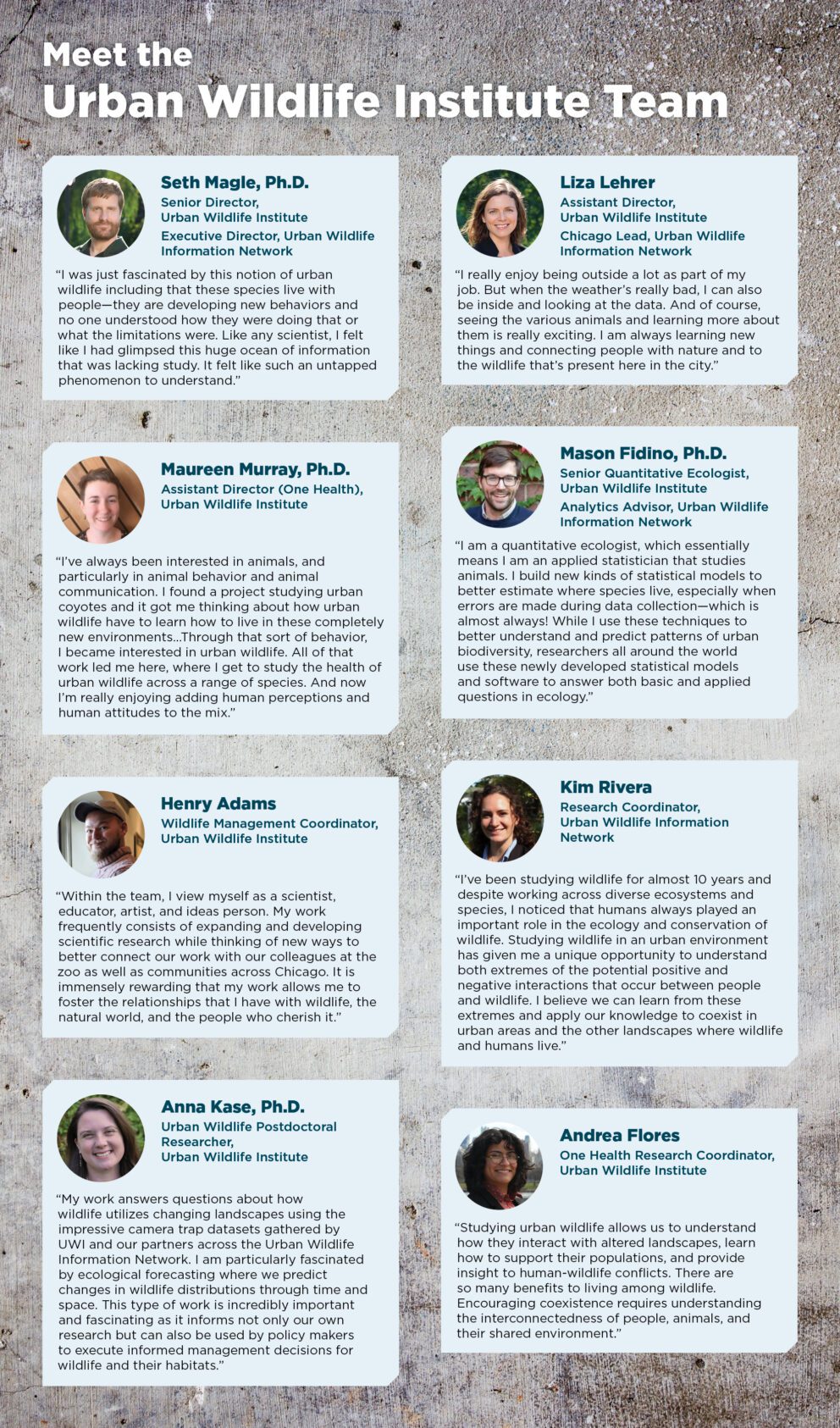

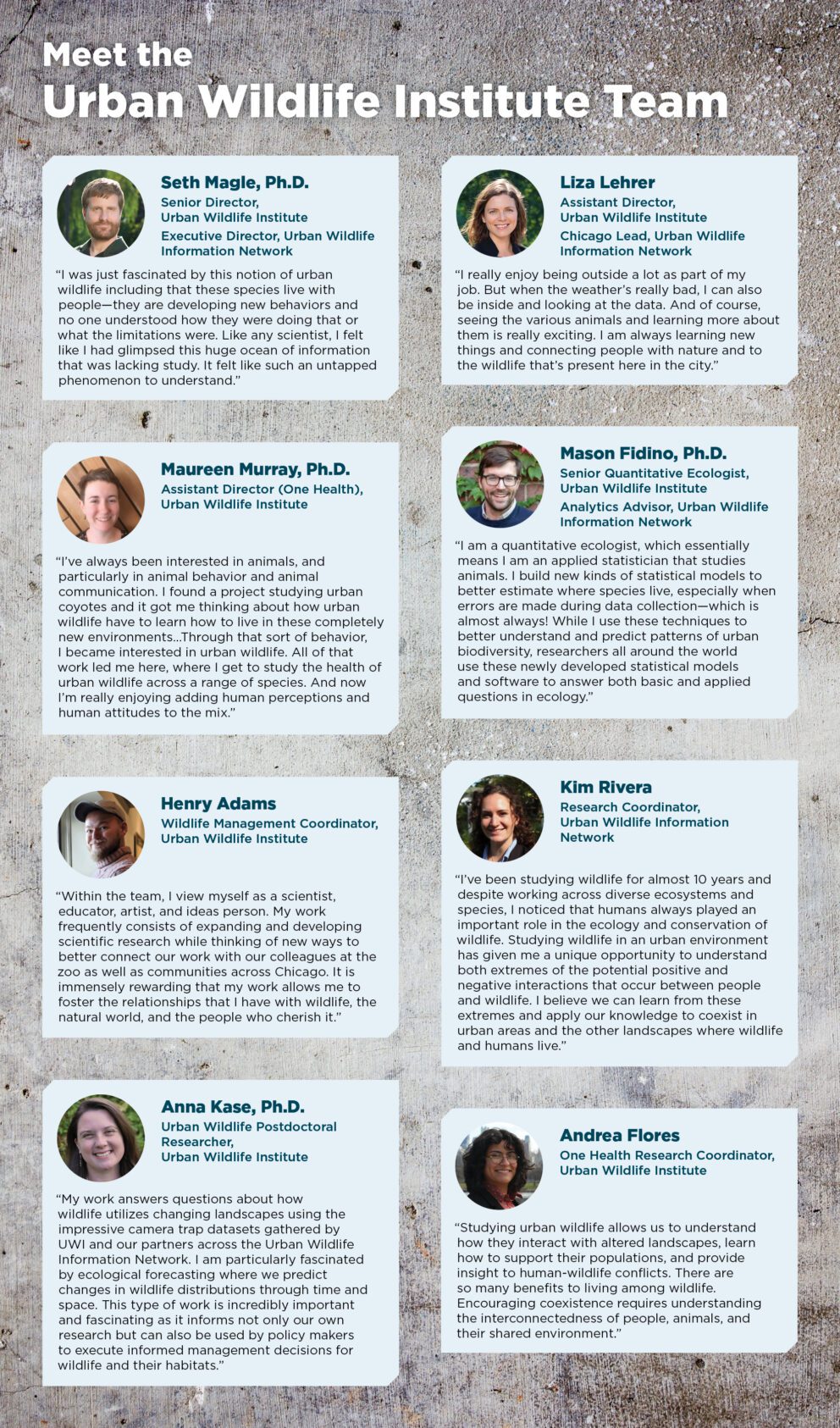

“The Urban Wildlife Institute is a group of researchers within the department of Conservation & Science at Lincoln Park Zoo,” explains UWI Assistant Director Maureen Murray. “We’re a small but mighty team that focuses on wildlife that lives in cities…We study a lot of different things about urban wildlife—where they live, when they’re active, how often they interact with people—and what people think about urban wildlife.”

“Small but mighty” is right. If you haven’t heard about UWI, it may be because you haven’t been paying attention. Did you hear about the Chicago Rat Hole? The news from Orkin that Chicago is the “rattiest city” in the U.S.? The red foxes that set up a residence in Chicago’s Millennium Park in 2023? If so, you may recall UWI researchers weighing in on these topics in various publications. Urban animals, after all, are their expertise—and as time goes on, more and more people are starting to rely on their information as we try to coexist with nature all around us.

The Origin Story

Lincoln Park Zoo created UWI in 2009. Zoo experts had the foresight to realize there was something this organization could do that the few others in the world studying urban wildlife—mostly at universities, testing very specific hypotheses over short periods of time—could not do.

“What nobody else had done, frankly, because it’s hard, was cast a really wide net to say we’re going to study many, many animals across many, many sites for many, many years—maybe forever, for as many years as we possibly can,” explains UWI Senior Director Seth Magle, Ph.D. “And a zoo is uniquely positioned to do that, because we’re not dependent on students to run our work. It’s not like we have to teach in the fall…We are available to study these animals, and really in a way that no one else has.”

In doing so, UWI could get a broad, integrated view of the urban wildlife community. With this information, it could inform the process of conservation in cities. Additionally, it can inform city planning and management to help create spaces that are friendly to wildlife as well as people. And it started this with a couple of major projects, including one that city residents now enjoy daily.

At around the time UWI began, the zoo was transforming a previous space at the South Pond into a wetland prairie ecosystem that soon became Nature Boardwalk, and the timing of both together is no accident. Previously, the area was a recreational, formal space devoid of natural plantings. Some may remember the swan boats that visitors used to take onto the water there.

It only made sense to turn this area into a space more conducive to wildlife. To that end, zoo staff worked to make the pond deeper, so that turtles and fish could spend winters in it, and added bubblers to ensure oxygenation and circulation. Native vegetation and trees were planted, while nesting structures for birds were added under a bridge. Today, many migratory birds use that space, along with turtle species and mammal species such as bats.

“So, it’s really being used by wildlife, and really it’s not just an important space for wildlife, but also a really important place for city dwellers to come and spend time in nature” Lehrer says. “And also find a place to really relax and find peace and solace in such a beautiful space.”

Today, Nature Boardwalk is an important living laboratory that can teach students and scientists a lot about diverse urban ecosystems, including how animals use urban habitats and ways we can mitigate human-wildlife conflict.

UWI also started one of its first projects by placing motion-triggered cameras along various transects radiating from the city into the suburbs to capture information and images of animals. Monitoring the small and large animals in these people-centric environments has yielded millions of images over the last 14 years and resulted in a wealth of information being used to deepen our understanding of the animals that share our space.

But over the years the center has expanded its scope even further. Today, it investigates bats, rats, black-crowned night herons, and ticks. It also works with the leaders of community gardens to explore ways to help their city plots bloom even more beautifully than ever. UWI has also embraced the One Health mindset, which believes that the health of cities, people, and animals are tied to one another.

What We’ve Learned About Urban Animals—And What We Still Need to Know

You may be surprised to realize that there are flying squirrels in the Chicago area—and they are thriving. Another species you may not have realized live here are mink, which are consistently found in small numbers in suburban areas as well as the city. Unfortunately, other species are declining in this region, like grey foxes. We know about these species and their population trends because of UWI.

UWI researchers have been able to identify some of the traits that help local animals like these survive. “They’re very intelligent, very adaptable—they’re able to change their behavior quickly, in order to take advantage of changing situations,” Magle explains. Smaller animals tend to be more successful in cities because they don’t need as much space to support them. Successful animals also tend to be generalists; they don’t eat just one type of prey, which makes it easier for them to find sources of food in concrete jungles.

Although UWI has been focusing on urban wildlife for some time, researchers have just scratched the surface on what there is to know about this topic. They continue to study how urban animals decide where to live and how they are able to persist in certain habitats but not others. In the meantime, UWI’s current research continues to break ground. For example, a recent publication confirms what urban wildlife scientists suspected—that more wildlife diversity happens in wealthy, gentrified communities versus underfunded ones.

However, it’s not that simple; the study also found that factors such as human population density make a difference. This isn’t just a step toward ensuring that we understand wildlife trends. This becomes an equity issue, given that research has proved that having positive experiences with wildlife and the natural world can reduce stress.

UWI continues to try to understand what brings interesting or desirable animals—like songbirds, foxes, and others—into cities, while discouraging the ones considered pests, like rats and pigeons. And in the future, the organization hopes to partner with those who have a role in policymaking, such as city planners, landscape architects, and developers, to “give wildlife a seat at the table,” as Magle puts it, when cities are being planned.

In other words, despite everything we’ve discovered since 2009, there’s plenty of work for UWI to do—and so much more to learn.